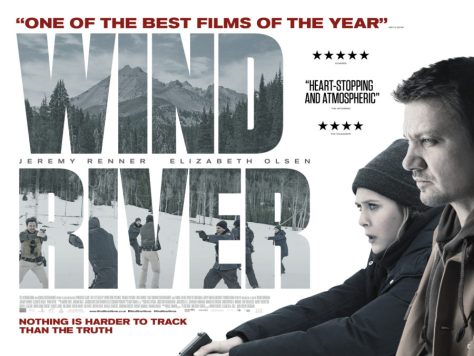

I’m not a parent. I’ve never seen a piece of myself shining in the eyes of a child. I can’t imagine what that is like, and I cannot fathom what it must be like to have it and lose it. I have lost my entire world to grief. When you go through it, there’s a pernicious lie you’re told in counseling, by people who don’t get it, by most of pop culture: it gets better. The pain goes away. It doesn’t. It does change. It changes you. The knife-sharp pangs that wrack you in the beginning become a dull roar. You learn to live around it, but the person you were before never comes back. It’s something you suspect as soon as you lose the person: I’m never going to be the same. The most honest assessment of the grieving process that I’ve ever heard comes from one grieving father to another in the most underrated film of 2017: Wind River.

Taylor Sheridan’s modern western crime thriller (it manages to tick all the requirements for at least three genres) was another spectacular script from the Sicario screenwriter and a very impressive directorial debut. As good as Gary Oldman was as Winston Churchill, I thought Jeremy Renner’s performance in this film was the best acting I saw last year. Renner is always strong, but to the detriment of his appreciation, his performances are usually understated character work. With Wind River he was able to blend his gift for nuance with a clear, deep connection to the material. The porch scene is so intensely honest that it nearly blew me out of the theater. It’s a testament to how entertaining the film is in the midst of dealing with the bleakest terrain a human soul has to cross that I was able to walk out feeling like I’d finally spent time with someone who got it. I wish I’d have gotten a counselor as good as the one Renner’s character got at that seminar in Casper.